KSHB 41 anchor/reporter JuYeon Kim covers agricultural issues and the fentanyl crisis. Share your story idea with JuYeon.

—

Black farmers in America continue to face severe disparities.

They make up less than 2% of all farmers and own less than 1% of U.S. farmland.

For generations, they faced systemic racism over land ownership, access to grants and equal wages.

According to data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service, the gross cash farm income for the average African American farm was roughly 85% less than the income for other farms between 2018 and 2020.

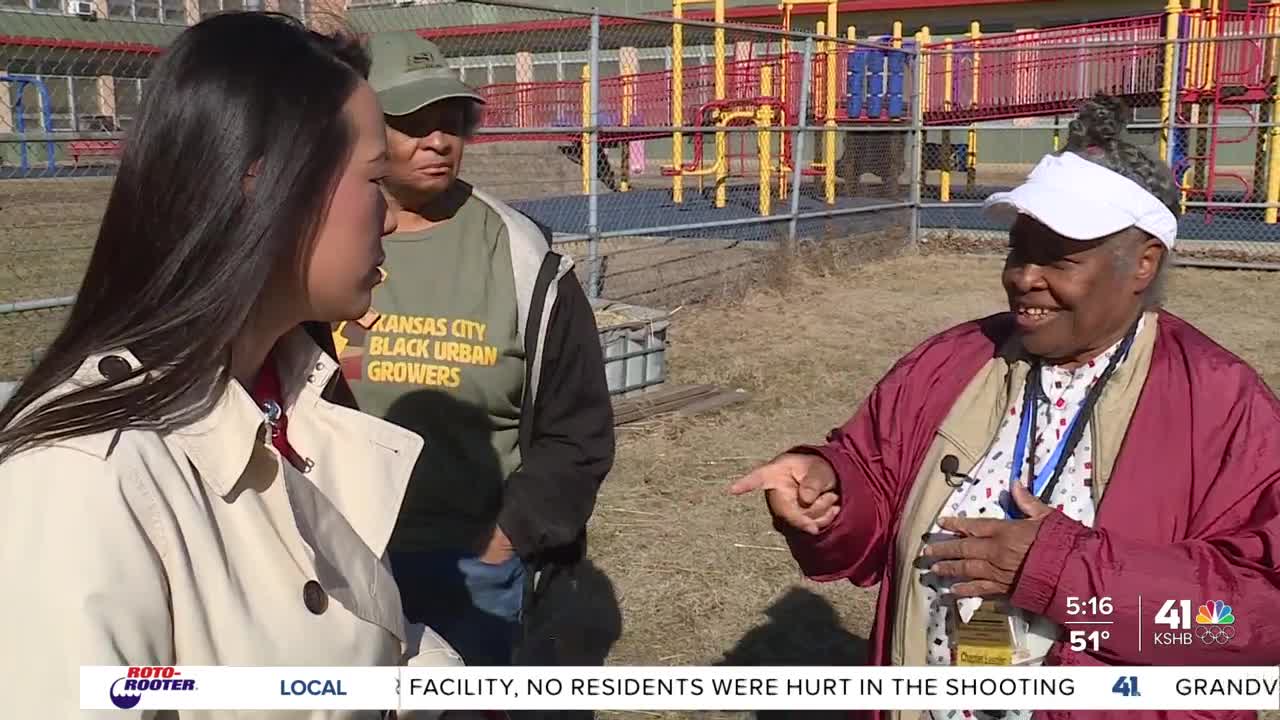

“All of a sudden, they started coming in and tearing down these little homes,” said Dr. Barbara Johnson, who lives and grows food in the urban core of Kansas City, Missouri.

Johnson has been fighting to keep her Kansas City neighborhood alive. She was 16 years old when her family settled there in 1961 after fleeing the Jim Crow South.

“If I’m 80, think about it. We’re not gonna be able to hold on much longer cause our younger people cannot afford the homes," Johnson said. "When the whites were moving in, they said to us, ‘We can’t have shared, we’re not gonna have shared driveways. We are not gonna share driveways.'

"So guess what the city did, okay? Take away our homes. And then blamed it on, ‘We weren’t keeping it up.’ No, we were just old, couldn’t afford it anymore. So they started making the senior facilities and, guess what, moving us in.”

It is a struggle dating back decades. Black farmers have lost millions of private acres over the last century, shrinking from 41.4 million acres in 1920 to 5.33 million in 2022, according to the USDA.

The loss of land is blamed on higher property taxes, lower wages, grant discrimination by the USDA and eminent domain. Johnson’s father lost his property in Knoxville, Tennessee, through governmental seizure.

“Can you imagine them walking in and says, ‘We’re gonna take away all that land you have that raised 14 of us?'" Johnson said. "And walk away from it for about $6,000 for all that land? It would be like taking all of this from my papa."

Life in Kansas City was better, but not easy. Even though Black Americans could buy homes, they could not garden on their own property. Johnson believes the government knew, even then, that if people could grow their own food, they could survive.

“As long as they can say we’re not being racists, we’re not discriminating, the lie works,” Johnson said. “We have got to take the land back, teaching our children to farm. Period.”

That is where Toni Gatlin comes in. Since 2010, the two women have been planting community gardens across Kansas City schools.

They officially launched their nonprofit organization last year, called Urban Green Dreams, and oversee five plots of community gardens.

“This is, to me, science, math, English, everything,” Gatlin said.

The women teach students how to grow food, protect the environment and become self-sustainable. The hope is that today’s youth will grow healthy, become educated, come back to the land and own it.

“The young Afro-Americans here say, 'Ms. Toni, you are taking us back into slavery time. Ms. Toni, why you gardening? You pushing us back,'" she said. “From the science of it, from the math of it, from the legal part of it, you need to look at agriculture as a broad career field.”

Reversing generations of discrimination will take time, but Johnson and Gatlin are planting seeds of change today in hopes of harvesting equality tomorrow.

“That’s why I’m so committed," Johnson said. "Food is the first order."

—