As new sources of renewable energy grow, there has been a large-scale effort to remove dams, which generate hydroelectric power, across the country.

Over the summer, the largest dam removal project in history broke ground in Northern California along the Klamath River as construction crews have been working to tear down the Iron Gate Dam, constructed in the 1960's. It is the most recent of more than 60 dam removals nationwide this year, according to the advocacy group American Rivers, which estimates there have been more than 2,000 dam removals in the United States in the last 90 years.

It might seem contradictory that in a day and age where renewable energy is at the forefront officials are advocating for dam removal, but data show while they may be good for energy, they are not great for the environment or those whose cultures rely on it.

"The Klamath River is part of our being; part of the fabric of who we are," said Barry McCovey, the director of Yurok Tribal Fisheries. "When the river is in balance, we are in balance, but when it's out of balance, the Yurok people tend to go that way as well."

The Yurok Tribe settled along the Klamath River thousands of years ago. Over the generations, it has been the tribe's lifeblood, providing its members with spirit, food, and purpose as the river has historically played host to the third-largest salmon run in the country. As such, tribal members became avid fishermen and women as their diet relied on the plentiful salmon that filled the waterway.

Over the last 60 years, however, those populations have dwindled mightily as the California Department of Fish and Wildlife federally listed Chinook salmon as threatened in 1999 after their populations in the Klamath fell by more than 85% since the construction of the Iron Gate Dam.

SEE MORE: Understanding why Native American religion is linked to land

This year, the state banned Yurok members from fishing along the Klamath altogether due to historically low salmon populations.

"It's affected not just me, my grandkids and my whole family, but all the elders around us," said Toni Rae Peters, a member of the Yurok Tribe who has lived on the Reservation her whole life. "There's not enough to feed my family."

"During a regular fishing season when we have enough fish to have a fishery here, there would be docks out here, there would be boats, and there would be a bunch of activity," added McCovey. "But it's fallen on hard times and everything is shut down."

According to National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association Fisheries, dams change the way rivers function as they can interfere with life cycles of various fish populations as they act as barriers to juvenile fish migrating to the ocean and adult fish returning to their natal streams to spawn.

There are more than 90,000 dams across the country, many of them constructed between 1910 and 1960 as the US entered a new age of engineering. At the time, dams were seen as engineering marvels that showcased human ingenuity as they created power, recreation, and drinking water. But they are pricey, and their licensing processes became cumbersome, so as time marched on, people started looking elsewhere for energy.

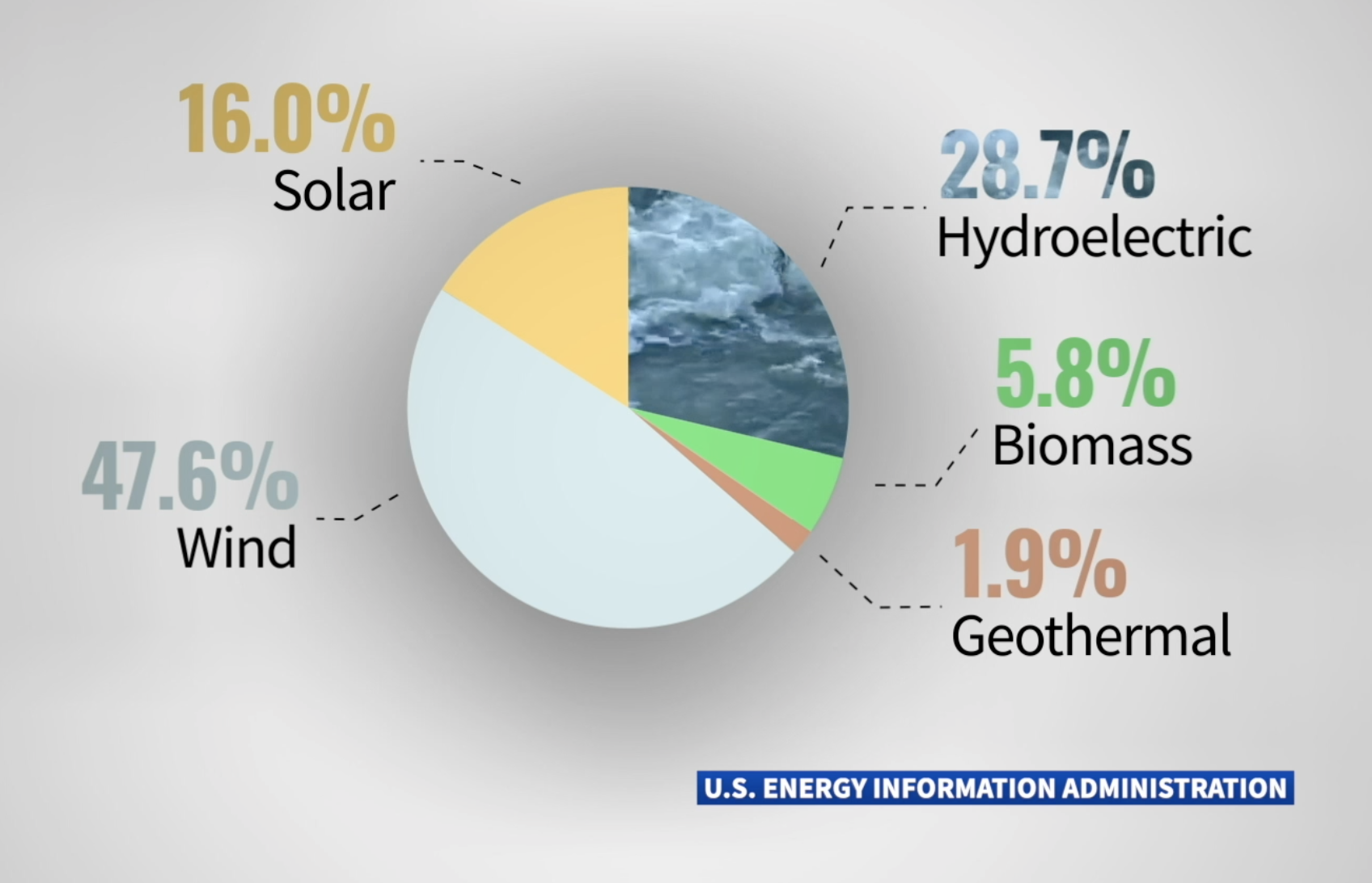

In the late 60's, hydropower was the only form of renewable energy used in the U.S. Today, it's only a cut of the pie as it comprises just over half of the energy output as wind energy alone and 28.7% of renewable energy altogether, according to data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

Add on the emerging data that shows dams disrupt natural habitats, emit more carbon than previously thought, and pollute rivers and streams and many dams became barren as companies stopped renewing their leases on them.

It has led us to where we are today as only 6% of dams are currently used to generate electricity, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. Most are used for irrigation, recreation, and drinking.

"[The Iron Gate Dam removal] has been a painstaking process from the perspective of scope and scale," said Mark Bransom, CEO of the Klamath River Renewal Corporation, the group heading the $500-million removal of the Iron Gate Dam. "I understand the opposition to the project. There are a number of people who have lived for years around these lakes who really value what these lakes offer, but I'm optimistic that we can foresee a time when a restored river brings a lot of values and appreciation for the environment that's going to result from restoring some sort of ecological balance to the area."

"I'm a native practitioner, but my main thing is I want to please our ancestors [by restoring the Klamath River] and that's how deep it goes," said Chemooch McCovey, a member of the Yurok Tribe who has devoted his time to helping restore the river by picking native seeds that will be planted along the river's shoreline after the Iron Gate Dam comes down. "It's generation after generation for thousands of years, but that's how important it is to us and our culture. It's epic."

There is a symbiotic relationship along the shores of the Klamath River: one between river and people.

It's a relationship that has been turbulent for quite some time, and finally on the precipice of healing.

"Our health: our mental health, our physical health, our spiritual health is also connected to the river," said Barry McCovey. "You know, we're just kind of building these sideboards, and then the river will go in and do all the hard work and work to heal itself, and as the river starts to heal itself I look forward to the Yurok people feeling good about that and hopefully having some catharsis and some healing ourselves."

SEE MORE: $9.5M allocated to Indigenous landscapes in Western Montana

Trending stories at Scrippsnews.com