This is the third of a three-part series by KSHB 41 News anchor Taylor Hemness on the 10th anniversary of a deadly fire that changed families, a community and a department. Read part 1 here. Read part 2 here. Taylor welcomes feedback on this series, which you can share by sending him an e-mail.

—

On Sunday, Oct. 12, the Kansas City firefighter community reflected on the 10th anniversary of a fire that killed Kansas City, Missouri, firefighters Larry Leggio and John Mesh, and injured two others so badly they were forced to retire from fighting fires.

The impact on KCFD of losing two men in one night was profound. The men and women who served in the department in 2015 still remember the tragedy.

But the department has also changed the way it fights fires in the last decade, including how to make sure firefighters stay as safe as possible while carrying out life-threatening work.

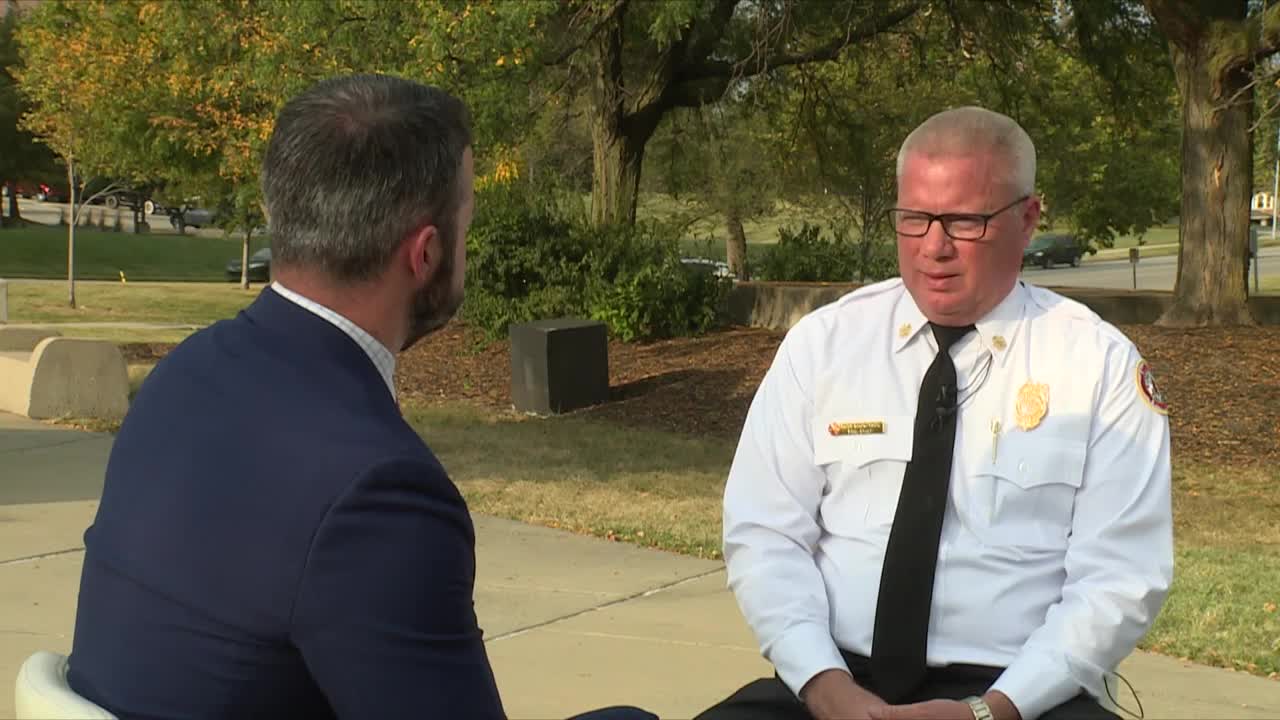

"It's everyone's worst nightmare to get the knock on the door, and that happened twice that night,” KCFD Chief Ross Grundyson told me.

VOICE FOR EVERYONE | Share your voice with KSHB 41’s Taylor Hemness

Grundyson was a battalion chief back in 2015, racing to the hospital when he got the call that two firefighters had been gravely injured.

"I remember being there and finding out it was John and Larry both," Grundsyon said. “I never thought John would be the guy something like this would happen to. It's what we fear the most."

That heartbreaking news was spreading through the department.

Michael Hopkins is a battalion chief today, but that night, he was one of the firefighters dispatched to the location near the corner of Independence Avenue and Prospect Avenue as the fire got worse.

"When we arrived on scene, a firefighter came up to me,” Hopkins said. “[He] came up and said that there'd been fatalities."

Hopkins and I spoke outside of what was John Mesh's fire station. I asked how a death in the department hits the individual station.

“It's devastating," Hopkins said.

Both Hopkins and Grundyson told me about moments every firefighter in the city likely lived out some version of that night.

"Immediately grabbing my cell phone and calling my wife and saying, ‘We've had fatalities. It's not me, I'm fine. I'll call you later,’" Hopkins said.

"It was very late that night when I got home,” Grundyson told me. “And I remember my wife met me at the door, and we just held each other."

The fire was eventually ruled an arson, set intentionally inside a nail salon in the building. More than two years later, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health released a lengthy report outlining what happened, including the department's response.

The report identified 16 recommendations all fire departments should follow, and that NIOSH investigators found to have played a part in this fire.

Mesh and Leggio died not in the fire itself, but when the exterior wall of the building collapsed on top of them.

"For us, one of the things that we really improved on immediately was collapse zones,” Grundyson told me.

The report defined a safe collapse zone as one that is equal to the height of the building, plus an allowance for scattering debris.

"We started using tape, and we started taping them off,” Grundyson explained. “And we started assigning people to make sure no one went across that and entered the collapse zone."

"We've always had them,” Hopkins said. “We've done a lot better job since that incident of enforcing those."

As I read the report, it struck me how much of it is about firefighters understanding the physical makeup of a building and how it’s constructed. I asked Grundyson and Hopkins about that part of a fireman’s job.

"That's why that building construction is a class now that's given to every captain and every battalion chief when they're promoted," Grundyson said.

Not only that, but being purposeful about cataloging that information. The report states KCFD had responded to the location for at least three prior fires. Individual fire companies had informal procedures, but they were never put into a formal format.

Another tactical change for KCFD in the last 10 years is the establishment of a safety officer. That's another recommendation listed in the report.

"Car 110's sole function is to observe the scene for safety hazards, and ensure if a collapse zone is set up, that collapse zone is being maintained," Hopkins told me. "They're there solely to be the eyes for safety. They also have the authority on the fire ground to just stop an operation. If there's not time to relay it, they can stop an operation right then."

But both Grundyson and Hopkins say maybe the biggest change for KCFD isn't in the NIOSH report.

“It was really the first time as a job that we addressed the mental health and understood,” Grundyson told me. “In the past, it had always been something where, well, you pull your boots on, go back to work and tough it out."

Hopkins told me he absolutely sees a difference in recognizing mental health in the department in the last decade.

"Really, after that incident, it just became more prevalent as a need," he said.

I reached out to IAFF Local 42, the Kansas City firefighters’ union, multiple times to get their thoughts on the fire and on Mesh and Leggio's deaths. They did not respond.

Grundyson recently announced he will retire from the department early next year.

Thu Hong Nguyen, the woman convicted of starting the fire in the nail salon, was sentenced to more than 70 years in prison. She’s serving that sentence in the Missouri Department of Corrections. She’s housed in the Women's Eastern Reception, Diagnostic and Correctional Center in Vandalia, Missouri.

—