This story is part of a series examining Kansas City's domestic violence court system during Domestic Violence Awareness Month in October. Upcoming coverage will include stories from survivors and advocates, as well as offenders who have successfully completed domestic violence court programs. Share your story idea.

—

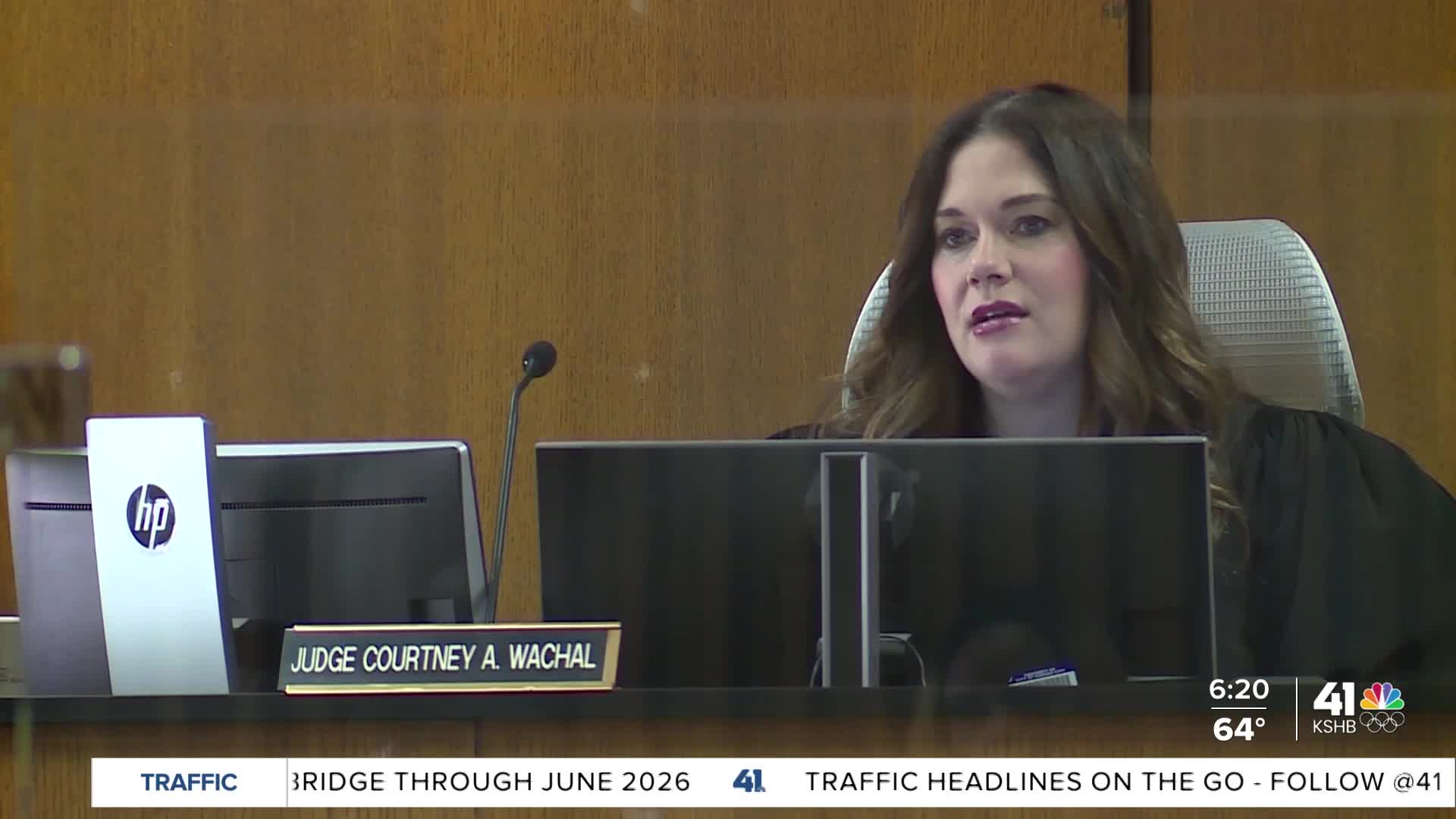

Kansas City Municipal Court leaders have created an unusual approach to handling domestic violence cases. One judge oversees thousands of domestic violence violations each month.

Court leaders say the process, which they call a "hub of judicial innovation," sets KC apart from court systems across the country.

Presiding Judge Courtney Wachal, of the 16th Judicial Circuit Court of Missouri-Kansas City Municipal Division, has exclusive jurisdiction over all domestic violence violations within Kansas City limits.

Wachal handles nearly 200 cases per day, Monday through Friday, starting at 9 a.m. in Division 203.

"This is a very serious problem in our city," Wachal said. "Kansas City is unusual in that more than 90% of domestic violence cases are filed in municipal court. There is no shortage of domestic violence cases filed here at this level."

Most domestic violence cases in Kansas City — everything from pushing to strangulation — are filed as ordinance violations in municipal court rather than as felonies or misdemeanors at the county level. They include intimate partner violence, child abuse, child endangerment, violations of protective orders, stalking and violence between family members.

Only the most serious cases, like homicide, reach the county level.

Wachal acknowledges the court system can feel like hoops to jump through.

"I think it's important we acknowledge in Kansas City, it's not easy," she said. "If you want to get to an order of protection, you have to go to the Jackson County Courthouse. If someone violates the order of protection, they receive the charge in [the] municipal courthouse. If they get charged with a felony, it's at the Jackson County Courthouse."

The court has adapted to the large caseload by creating specialized programming targeting people with the greatest potential to change and stop the cycle of violence.

- Compliance Docket (2015)

- Relationship and Sexual Violence Prevention Docket (2022)

- Early Intervention Bond Class (2022)

- Fathers for Change (TBA)

Statistics show these programs are working.

The court also provides wrap-around services for intimate partners when programming is not successful with the person charged with domestic violence.

"We are trying to reach the people where they are at so they have the programming they need to stop this cycle," Wachal said. "If I jailed every single domestic violence offender, they would be released after four months, they would be angrier at their intimate partner than before and would likely reoffend because they have not had anything to disrupt the cycle of violence."

In this court setting, the maximum punishment for a domestic violence offender is six months in jail, per charge. For more on fines associated with the Kansas City Municipal Court, click here.

Part of the solution involves moving more cases to the county and state level. Jackson County Prosecutor Melesa Johnson has committed to taking on more serious cases.

"I'm so proud of Prosecutor Melesa Johnson, who's indicated she's going to start filing more of these as felony cases," Wachal said. "The court is constantly innovating programming to try to address it, but some of these offenders do need to be charged with more serious offenses."

Wachal believes the court is doing a better job of closing the gaps between city and state courts and identifying which cases should be handled at which level.

"If we can impact someone on a two-year probation, rather than send them to jail, it's a much more meaningful outcome," Wachal said. "It also means that people who shouldn't be at this level, they would go to prison because they are a genuine public safety risk and risk for domestic violence homicide."

The consequences of domestic violence can escalate quickly. Kansas City has recorded 18 domestic violence homicides this year, compared to 12 for all of last year.

Scotty Dennis knows these consequences firsthand. His daughter was murdered in 2017.

"I miss my daughter. She left behind five kids. She was shot in the back of the head [while] leaving, walking out of her bedroom," Dennis said. "If you see something, say something. Domestic violence is serious; murder is serious. Because if not, you are going to be in my shoe, and this clown suit is one size fits all. It doesn't discriminate, it don't care where you come from."

The average victim of domestic violence goes through the process eight times before following through with prosecution. Wachal says she is creating an environment where the court is always ready to hear them.

"It's very frustrating by everyone involved when these cases don't get prosecuted," she said. "I understand why, because these cases are so complicated, but I think creating an environment that we are a court that's trying will increase prosecution rates eventually."

The Kansas City, Missouri, Police Department says handling domestic violence cases requires "very open communication" with the municipal prosecutor.

Additional information on the process of referring domestic violence cases was shared by a KCPD spokesperson in the statement below:

"Many cases are still referred to the Municipal Prosecutor as this is the most appropriate disposition for many comparatively lower-level offenses (minor injury, low numbers of reported offenses, etc.). Understanding there are often unreported prior incidents, prosecution still requires probable cause and reported history is a part of their consideration for State charging. However, our partnership with the Municipal Prosecutor involves very open communication and, if/when the Municipal Prosecutor is concerned a case should be reviewed for potential State filing, the process exists to – in short order – halt a city charge and pursue further investigation into potential State charges when appropriate. Conversely, the State will also return submitted cases back to KCPD for filing at the Municipal level when their criteria are not met."

—

KSHB 41 reporter Megan Abundis covers Kansas City, Missouri, including neighborhoods in the southern part of the city. Share your story idea with Megan.

This story was reported on-air by a journalist and has been converted to this platform with the assistance of AI. Our editorial team verifies all reporting on all platforms for fairness and accuracy.